Left or right arm? New research reveals why vaccination site matters for immune response

2025-04-29T08:56:00+10:00

Senior authors Mee Ling Munier (middle) and Anthony Kelleher (right) in the Kirby Institute laboratories with Stuart Turville.

Photo: Kirby Institute

Scientists have uncovered why vaccines can elicit a stronger immune response if they are administered in the same arm.

Sydney scientists have revealed why receiving a booster vaccine in the same arm as your first dose can generate a more effective immune response more quickly. The study, led by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research and the Kirby Institute at 91╠Į╗© Sydney and published in the journal , offers new insight that could help improve future vaccination strategies.

The researchers found that when a vaccine is administered, specialised immune cells called macrophages became ŌĆśprimedŌĆÖ inside lymph nodes. These macrophages then direct the positioning of memory B cells to more effectively respond to the booster when given in the same arm.

The findings, made in mice and validated in human participants, provide evidence to refine vaccination approaches and offer a promising new approach for enhancing vaccine effectiveness.

ŌĆ£This is a fundamental discovery in how the immune system organises itself to respond better to external threats ŌĆō nature has come up with this brilliant system and we're just now beginning to understand it,ŌĆØ says 91╠Į╗© Conjoint Professor Tri Phan, Director of the Precision Immunology Program at Garvan and co-senior author.

Scientia Professor Anthony Kelleher, Director of the Kirby Institute and co-senior author, says: ŌĆ£A unique and elegant aspect of this study is the teamŌĆÖs ability to understand the rapid generation of effective vaccine responses. We did this by dissecting the complex biology in mice and then showed similar findings in humans. All this was done at the site of the generation of the vaccine response, the lymph node.ŌĆØ

How vaccination site matters

Immunisation introduces a harmless version of a pathogen, known as a vaccine antigen, into the body, which is filtered through lymph nodes ŌĆō immune ŌĆśtraining campsŌĆÖ that train the body to fight off the real pathogen. The researchers previously discovered that memory B cells, which are crucial for generating antibody responses when infections return, linger in the lymph node closest to the injection site.

Using state-of-the-art intravital imaging at Garvan, the team discovered that memory B cells migrate to the outer layer of the local lymph node, where they interact closely with the macrophages that reside there. When a booster was given in the same location, these ŌĆśprimedŌĆÖ macrophages ŌĆō already on alert ŌĆō efficiently captured the antigen and activated the memory B cells to make high-quality antibodies.

ŌĆ£Macrophages are known to gobble up pathogens and clear away dead cells, but our research suggests the ones in the lymph nodes closest to the injection site also play a central role in orchestrating an effective vaccine response the next time around. So location does matter,ŌĆØ says Dr Rama Dhenni, the studyŌĆÖs co-first author, who undertook the research as part of his Scientia PhD program at Garvan.

Clinical study validates findings

To determine the relevance of the animal results to human vaccines, the team at the Kirby Institute conducted a clinical study with 30 volunteers receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Twenty participants received their booster dose in the same arm as their first dose, while 10 had their second shot in the opposite arm.

ŌĆ£Those who received both doses in the same arm produced neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 significantly faster ŌĆō within the first week after the second dose,ŌĆØ says Ms Alexandra Carey-Hopp├®, co-first author and PhD student from the Kirby Institute.

ŌĆ£These antibodies from the same arm group were also more effective against variants like Delta and Omicron. By four weeks, both groups had similar antibody levels, but that early protection could be crucial during an outbreak,ŌĆØ says Dr Mee Ling Munier, co-senior author and Vaccine Immunogenomics group leader at the Kirby Institute.

ŌĆ£If you've had your COVID jabs in different arms, donŌĆÖt worry ŌĆō our research shows that over time the difference in protection diminishes. But during a pandemic, those first weeks of protection could make an enormous difference at a population level. The same-arm strategy could help achieve herd immunity faster ŌĆō particularly important for rapidly mutating viruses where speed of response matters.ŌĆØ

Looking ahead

Beyond the potential to refine vaccination guidelines, the findings offer a promising avenue for enhancing the effectiveness of vaccines.

ŌĆ£If we can understand how to replicate or enhance the interactions between memory B cells and these macrophages, we may be able to design next-generation vaccines that require fewer boosters,ŌĆØ says Prof. Phan.

This research was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Media enquiries

Luci Bamford, Kirby Institute, 91╠Į╗© Sydney

Related stories

-

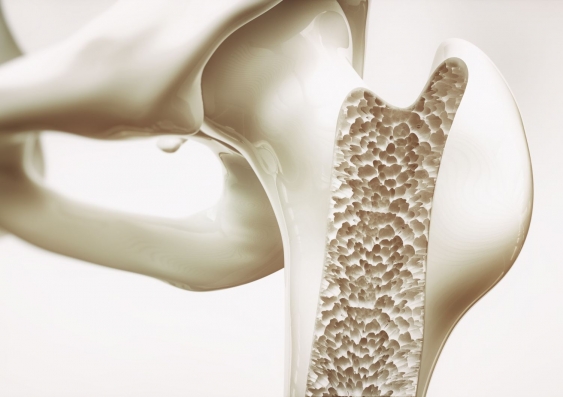

New type of bone cell could reveal targets for osteoporosis treatment

-

Trust matters but we also need these 3 things to boost vaccine coverage

-

Too many Australians arenŌĆÖt getting a flu vaccine. Why, and what can we do about it?

-

The power of peer-to-peer communication in the COVID-19 vaccine rollout: study